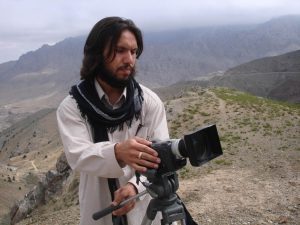

Zabihullah Noori is a multimedia journalist from Afghanistan who came to the UK as an asylum seeker in 2011. After being granted refugee status in 2012 and struggling to find work in his field, he began working as a translator and interpreter for immigration law firms. He joined the Refugee Journalism Project as a participant in 2016, and is currently based in London, where he works a TV station broadcasting to the Persian-speaking community and diaspora in Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan.

Words by Emma Djilali

You trained and worked as a journalist in Afghanistan – can you tell me a bit more about your work there?

Noori: I initially started as a translator/office manager for a media organisation. I then worked in positions as a reporter, editor, and eventually a news director. Originally, I am from the north, in a city called Mazār-i-Sharīf, but my work with different organisations required a lot of travel. For instance, I worked for one international organisation as a communications specialist, which required me to cover 17 provinces of the country [Afghanistan has 34 provinces]…so I have covered more than 50% of the territory.

You must speak multiple languages then!

Noori: I know two of the official languages of my country – Deri and Pashto. I spent some time as an undocumented refugee in Pakistan, so I picked up Urdu there. I know Farsi and, because my wife is Uzbek, I know a little bit of Uzbek and…this broken English that you are hearing. [Laughs]

It doesn’t sound broken to me! Could you tell me a bit about your experience arriving in the UK? What was it like trying to find work as a journalist?

Noori: Well, within the asylum process you’re not allowed to work – that is, you are not allowed to do any paid [or contractual] work. Nowadays [the British government] has limited voluntary work as well. When I came here I was allowed to do some volunteering in the council where I was based, in Manchester. I approached them and told them I was interested in setting up a community newsletter. They agreed, and I worked with them to set up the first two issues. I also wrote some articles then – so that was good.

But when I moved to London, I tried to apply for different jobs in media and…navigating my way through the system was the hardest thing – when I was in the United States, I knew the system there. In Afghanistan – I knew the system. Same in Pakistan. But when I came here, I was kind of lost. I didn’t know which approach to take in order to find a position in journalism.

So I applied for various jobs the conventional way, you know, just sending my resume…and nothing happened. I never heard back from 90% of applications. This was when I said, “Okay, if I keep looking for work in my field and I don’t get anything, I might become destitute.” I thought: let’s try something else. That’s how I began working as a translator.

How did you find out about the Refugee Journalism Project?

Noori: It was a coincidence because one of the firms I did translation work for was the Migrants Resource Centre, which partnered with the London College of Communication for [this] project. One day one of the solicitors said, “Hey, you’re a refugee and you’re a journalist – why don’t you apply for this project?” And so I got into contact with Vivienne Francis [the director of the RJP] through e-mail and she welcomed me and…that’s how I became involved.

And how has the project helped you, professionally speaking?

Noori: The basic help that the project offered me and other journalists was to show us how to approach the industry. All of us [participants] came from a journalistic background…but we didn’t know how to approach organisations [here]. It’s like you’re having the key to the Ferrari, but you don’t know how to drive, and you’re stuck there! In this sense, the project was very helpful.

For instance, a friend and I… [through the project], we both got internships with Thomson Reuters Foundation. After that, we were offered freelance positions with them. So that’s how it worked – as a result of the networking.

You know, I might have even applied to the TRF before [joining the project]…I don’t remember because I applied for hundreds of jobs – but I never heard back, even for freelancing positions.

In what other ways would you say the project has been an enriching experience?

Noori: Most of the journalists who came to the programme had been away from the field for quite some time. For instance, when I came here, I was not allowed to work for one year, and that year created a gap. So, when I applied for jobs, they might have seen my CV and said, “Oh – he was away for one year… let’s forget about him, let’s find someone with recent experience.” That’s one thing.

So, the workshops were useful [in terms of] getting us back up to speed… But most importantly, the connections were very important – not just with people in the industry but also with other [exiled/refugee] journalists who were in similar situations…learning from their experiences and the mistakes they made. Each one of us had some kind of experience that was helpful for others, and it was [the project] that brought us together and created this little community of journalists in diaspora.

Do you think that your refugee status has impacted the way you (or others) are treated within the British journalism industry?

Noori: Well [the differential treatment of refugees] is happening on the whole, there’s no doubt about it. But in journalism specifically – it’s hard to say yes or no. I don’t know, maybe if I was ‘John’ something or ‘British Name’ something, I might have been called for more interviews. But the fact that my name is Zabihullah Noori and [has] an Arabic tone to it, that my resume says clearly that I come from Afghanistan…I think, maybe that could part of it – but I have no idea.

Again, the point is that it comes to networking, you know? Even though I might have arrived thinking, “Yeah, I’m really good at my job!” – no one knew me, and they wouldn’t bother to see the footage from Afghanistan to know how well I did my job back home. They want to know: “have you worked with any of the TV stations in the UK? Do you know anybody here [in the industry]?” No. We have no [British] references, no recommendations…this might be one of the reasons we [as foreign journalists] struggle.

But on the other hand, foreign journalists also have a lot to contribute to British media.

Noori: Yes – as journalist from abroad, I have to emphasize this one: we bring a lot to [British] society; whether it’s knowledge about [other] cultures – let’s say Syria, for instance. Lots of people who report on Syria don’t know a lot about it.

If they know their knowledge is limited to some of the pieces which they have read in the news, or a couple of books – the author of which might have spent a week in Syria and came back and wrote it. It happened to my country, in Afghanistan.

I know people who have been there, in Afghanistan, for three weeks. They meet with some people, take some field notes. Then they come back, and write a book – it’s a bestseller. But, if you really go in, deep into that one [book], some of the factual errors – and the lack of contextual knowledge – will stick out. But it’s still well received in the Western society because it has the right formula, the right ‘spices’, you know?

If we [refugee journalists] bring our perspectives in the newsroom, I’m pretty sure it will enrich the knowledge of our colleagues, as well as make it better in terms of fair and balanced reporting. People often get the facts wrong or they’re like ok, it’s this or that – it’s black or white. There is [in fact] a grey area and refugees are the ones who can teach you in terms of what these grey areas are, in terms of how sensitive different topics are.

In terms of next steps – do you see yourself continuing to work in TV, or do you have other goals in mind?

Noori: As a professional I would like to continue to work in media, and television. But at the same time…I would like to be in a position of more managing media rather than just going out in the field and doing the interviews. I’d like to be in a role where I am helping to set the goals, the agenda of the organisation and at the same time teaching. By teaching my intention is to share some of my experiences with students who have never been exposed to migrants and who have never known about any refugees coming with, I would say, more…more reputable backgrounds.

Because in this society, many people still see a refugee as someone who fled their country, who might be illiterate or who might ‘know’ very little, while in fact there are many people who have come, who had to come to this country solely because their life was at risk. They left a very good position back home, their society, social connections – everything. They came here and now they’re wandering around ‘doing nothing’ because the system poses some sort of restriction on them. And then on top of that, society doesn’t receive them well.