Kerim Balci mulls over the passing of the old guard to the new at the UK’s only longform and narrative gathering, CIJ’s Well Told festival.

“Storytelling can change the world,” read the cover of a book by Ken Burnett, embellishing the showcase of a charity shop that stood between my office and my favourite kebab house in North London. The rather dull cover pulled my attention into the unread book each time I passed by, and the idea of storytelling being a positive force for social change busied my mind the rest of the day.

This was back in 2016. Having lost the lengthy battle for the souls of the Turkish people to the authoritarian regime of the country, I had already started questioning whether journalism mattered at all. After all, we were certainly the most read newspaper of the country and yet we couldn’t convince our own readers that the country was leading towards a dictatorship. The dictator-to-be, on the other hand, was able to mobilize millions with his fictitious stories.

Maybe it was storytelling and not reporting that would change the world?

All that mathematics of news writing, the pyramid, the double-fact-checking, the objectivity tests meant nothing to the general public. We were telling the truth, and yet they were believing a well told lie.

Maybe it was storytelling and not reporting that would change the world? The dictator-to-be, on the other hand, was able to mobilize millions with his fictitious stories.

It all came back to me when I heard Jeff Maysh, a true crime longform writer, tell the audience at the Well Told Conference that “Truth is stranger than fiction, but it has pacing issues…”

Jeff was talking about why, when well told, the story of truth would attract more public attention, and Hollywood money, than pure fiction.

Jeff was talking about why, when well told, the story of truth would attract more public attention, and Hollywood money, than pure fiction.

What Maysh called ‘pacing issue’ corresponds to the chronotope of Mikhael Bakhtin, or a lack of it.

Chronotope is the interconnected representation of time and space in a novel or a movie.

It engulfs us into it so much so that when reading a novel, or watching a movie, we experience a new time-space reality and do not bother that decades pass in a few pages or minutes. Chronotope is completely lacking in journalistic writing.

Time and space, when and where, are, for us, a part of the content, not of the form.

Longform journalists do…

“Longform is the superior format,” said Maysh. “This is the new normal!”

“Era of infotainment!” disgusted the old journalist in me. “But then, who is the author?” outcried my literary critic self.

We, the shortform journalists, inform the readers about time and space. We don’t invite them to a travel therein.

This second question is a beautiful one, with no convincing answer. It is hermeneutics par excellence! If considerations like entertaining the reader, attracting attention of Hollywood producers, or even editorial satisfaction enter into the mind of the journalist, isn’t this a form of partnership in authorial position? I remembered, with an irk in my heart, the economy page correspondents who bylined generic texts sent to them from PR departments of major companies.

When Alex Perry, himself another longform writer, asked Maysh how the willingness to appeal documentary and film producers influenced his selection of what to write and what not to, Maysh claimed that both journalists and Hollywood were looking for the same thing:

“We want transformative characters, a strong narrative and a twist with some humour.”

Is this true? Or is it that Maysh and other longform journalists turned our esteemed profession from being the “first draft of history,” into being a “first draft of a Netflix soap opera”?

That power to carry the context with the text will eventually turn longform pieces into immortal pieces of art

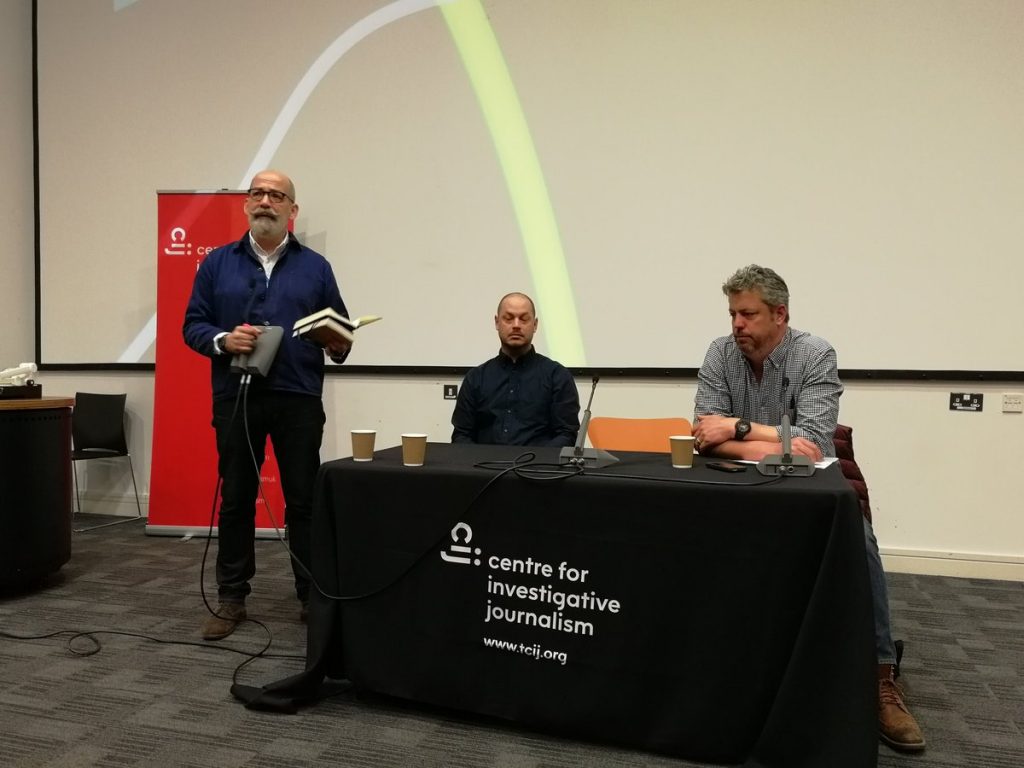

James Harkin, founder of the Centre for Investigative Journalism is no longer concerned with being the first draft of history. “We have lost that position to social media already,” he told the audience while speaking about how investigative journalism meets story.

According to him, being a second draft is in fact an opportunity. As literally no journalist was left on the ground, what we journalists were giving order and form to was no longer the half-ordered world of events, but the infinitely disordered world of first impressions in the social media. Of course, in this world of information bombardment, “we have to be endlessly sceptical about who is feeding us a story.”

Longform, according to Harkin, is a slower kind of journalism which builds context. That power to carry the context with the text will eventually turn longform pieces into immortal pieces of art.

A conventional newspaper item dies with the new dawn and turns into archival material. A longform carries its time and space with it, and invites the reader to experience that chronotopic shift from the reader’s own time-space to that of the text, time and again.

A major difference between literature, particularly poetics and journalistic writing is that the meaning of a journalistic text is what it tells to the reader, whereas the meaning of a literary text is realized in what it does to the reader.

Reading a novel is an experience, it takes place at the same ontological level with the reader, whereas reading a news item is an epistemological exercise.

Or it was…

With longform, podcast, gamification of news, 360 degrees, VR and AR integrated news telling strategies news have become experiences themselves. This was precisely what BBC’s VR Studio’s Zillah Watson, speaking at the Interactivity vs Storytelling session meant when she said, “VR is experiential: audiences are able to see or feel an experience for themselves, it takes audiences on an epic journey.”

This will turn news into re-readable pieces of art and the readers into users. The “users will engage and revisit stories where they can pick characters and stories,” Ben Fogarty, CEO of Holoscribe.com affirmed.

That power to carry the context with the text will eventually turn longform pieces into immortal pieces of art.

The question that intrigues me here is whether the longform, podcast, VR or 360 are new opportunities or new demands of the entertainment industry? If the demands of the entertainment industry dominate the thinking and representing strategies of the journalist, who the real author is?

Gadamer would argue that the author and the text are both creative acts of the cultural milieu. Bakhtin would say ‘the author is a collectivity.’ Stanley Fish would say ‘the reader is the author.’ Nietzsche would half-agree, nodding, ‘the author is dead!’

All these questions attained a new dimension when Will Storr, author of the best-selling Selfie: How the west became self-obsessed, closed the Well Told Conference by telling us that we could not possibly escape from storytelling, as “the human brain is a storyteller.”

The brain analysis external stimulus, or data as Storr’s preferred term; it picks, orders, and makes a cognizable story out of pure data. In doing that, Storr claimed, our brains were not interested in facts, but in changes: “And great journalism is about connecting moments of change.”

At the happy 20th century of journalism, we, the old-guard, always thought of ourselves as reporters, not writers, or authors. We didn’t imagine things, we observed them. And yet, here, the proponents of narrative journalism, who claimed that Hollywood guys were “the saviours of journalism”, were telling us that we indeed do give order to facts in a creative manner.

To my old journalistic self, Storr was not only guilty of novelizing journalism, he also gossipised it. “That’s exactly what journalism is: gossip,” he acclaimed. The problem here is not accrediting a moral superiority to journalistic writing. Gossip is intrinsically an interim, and in-between phenomenon. There is no author of gossip, and certainly no editors, no fact-checking, no rules. Gossips are collectively created and the interaction between the gossipers are much more definitive than the facts or presumptions that are exchanged on the shape of the final product. The question is the same: Who does the gossip?

While leaving, half broken about the demise of the kind of journalism I knew and loved, half energized with the new horizons opened in front of me, Ken Burnett’s book title came to my mind again: “Storytelling can change the world.” It was now accompanied with publisher Martin Hickman’s observation that the transition from a traditional reporter into a longform writer was “as profound as going from a sprinter to a marathon runner.”